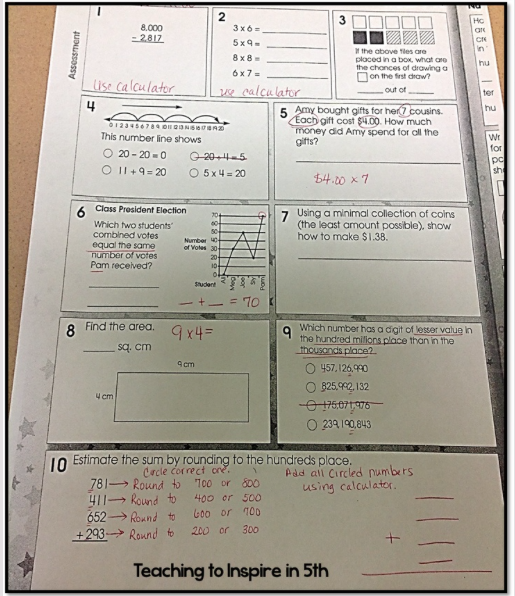

INSTEAD: If the mistake didn’t interfere with the meaning of the text (like if it was ‘a’ for ‘the’ or ‘fine’ for ‘fun’) let it go.

Do. Not. Interrupt. Your. Child’s. Reading.

Period.

How would you feel if you were putting your heart out on the line, trying something you weren’t totally comfortable with, in front of someone who you were afraid would challenge you, only to have that person stop you, interrupt your flow, and make you start over before you even finished? Over and over and over again?

Right. So that’s why if your kiddo’s reading and makes a mistake in reading a word, let it go. We want our kids to be comfortable reading with us–we want them to feel safe–so let it go.

Just make the correction when you read it the next time.

DON’T SAY: Speed up! OR Slow down!!

DON’T SAY: Speed up! OR Slow down!!

INSTEAD: Model appropriate pacing and fluency.

Fluency–or reading with appropriate speed, pacing, and intonation–is something that is best taught through parent or teacher modeling and tons of reader practice. Seriously. Fluent reading sounds like conversation, or natural speaking, and it’s something that has to be learned.

So if your kiddo is a total speed-reader or if, at this point, she’s as slow as molasses, it’s time to switch gears. Grab a level-appropriate book and say, Hey! I found this awesome book for us, and it’s going to be our book this week. We’re going to read this book until we become experts on this book– we’ll be book-reading super-stars by the end of this week, mark my word. . .

And the first day, you read the whole thing in its entirety. And then do an echo read, page by page. An echo read is really just like an echo–a portion of a text is read and then re-read by a second person (or class if you’re in the classroom). You can echo words, phrases, or whole pages. In this case, with an early-emergent text, it’s great to echo read page-by-page. First, you read a page and then your emerging reader reads that same page. And then you read the next page and she reads that very same page, like an echo.

And on day two, you read it in its entirety the first time, and then together, you echo read every two pages. Or every three pages.

Day three, you read it the first time, and either echo read by three pages or try a chorus read. A chorus read is where you read it together, in unison, like a chorus. Sometimes these are hard, but for pacing, it helps.

Day four, you read it the first time then hand the book over to your kiddo for an entire kid-read. Give her specific praises for her super-star parts: I really like how you paid close attention to the punctuation here (point to the specific part). You noticed the question mark, and you knew that meant that [the character] was asking a question, so you made your voice go higher at the end. Awesome.

Maybe on day four, you can tape yourselves reading or put it on video (not a big deal–just grab your flip cam or camera–it doesn’t have to be a huge, complicated video production) and talk about what sounded great and what you both need to work on.

Day five, it’s showtime. You both give yourselves ‘practice reads’– start by reading the book yourself and then give it to your child. Then it’s the BEST READ EVER–you both get to go on ‘stage’ for the most awesome, perfect, wonderful read ever. Video tape it, audio tape it, or Skype-read with your faraway aunts, cousins, grandparents, or friends. You both practiced all week–now show off your skills!

DON’T: Laugh.

DON’T: Laugh.

INSTEAD: Think about something serious and ugly and breathe deeply until you regain composure.

Even if your kiddo replaces ‘bat’ with ‘butt’ or ‘fact’ with ‘fart’ don’t laugh. The fastest way to kill confidence is to have the person a kiddo loves and trusts the most laugh in his face.

If you can laugh together, that’s one thing; most likely if your kid is reading aloud and says ‘butt’, he’ll break out into hysterics and you will too. But if he’s working hard, concentrating, and trying his best and still managed to make a mistake that tickles your funny bone, then just move on.

DON’T SAY: You know this. . .

DON’T SAY: You know this. . .

INSTEAD SAY: What part of the word do you recognize? If you get no response, say, Do you recognize this part (point to the beginning chunk or letter) or this part (point to the ending chunk or letter)?

Three things here:

1. If the kid knew it, she would have read it.

2. We all hate to be reminded that we knew something but forgot it.

3. By picking out

two parts of the word, you’re setting her up for success. It all goes back to

the choices thing that really helps with kids. Most likely she will recognize either the ‘b’ or ‘-at’ part of ‘bat’ or the ‘th’ or ‘-ick’ parts of ‘thick’. If she can pick up either part, say,

You got it! That does say ‘ick’. Now let’s put the first part, (give it to her and pronounce it)

‘th’ together with ‘ick’: th-ick. Thick!

Then put that new word into the sentence and give her a high-five for getting through it.

DON’T SAY: You’re wrong. That says, . . .

INSTEAD SAY: Nothing. Really. Remain silent. As hard as that may be.

It goes back to the very first thing I said about stopping kids as they read and making them re-read.

Let. Them. Read.

And unless it’s a mistake that interferes with the meaning of the text, let it go. And even more importantly, if every time your child gets stuck, he looks at you and you give him the word, then he’ll have a pretty easy time reading with you and won’t get to practice any decoding skills.

Now, that being said, if he did make a huge meaning-changing mistake, at the end of the page, go back and say,

- Are you correct? (And if he says Yes! then say. . . )

- Read it again and check closely. (If he reads it again incorrectly, say. . . )

- Can you use the picture to help you figure it out?

- Does it make sense?

- Does it sound right?

(And if he looks at it again and still misses the error, say. . . )

- Can you find the tricky part? (And if not. . . )

- It’s in this line.

- I’ll point it out and help you find it. (And then go back to pointing out the two chunks he may know. . . )

After kids become more comfortable reading with you, then hit them with an Are you correct? every so often on a page that he did read correctly. It’s not to make kids think you’re a pain in the neck; it’s to help them become better self-monitors. And as self-monitors, we’re constantly checking and re-checking to make sure that what we read made sense.

(re-posted from http://teachmama.com/)